In recent history, the official inflation rate in Zimbabwe averaged 43 percent from 2009 until 2023, reaching up to 786 percent in May 2020. These numbers are devastating, but the real hyperinflation happened pre-2009. Although initially stable, problems in the Zimbabwe economy emerged as early as the 90s due to a combination of factors including mismanagement, corruption, and controversial land reform policies. During this time, the Zimbabwean dollar rose rapidly, and inflation peaked at 79.6 million percent in November 2008.

In this article, we explain how Zimbabwe got to hyperinflation, stayed in that situation for so many years, and what lessons can be learned from it.

What Is Hyperinflation?

Hyperinflation is generally characterized by an inflation rate of greater than 50% per month. It rapidly erodes the value of a currency, which leads to economic stagnation, price volatility, and distrust of government monetary policy and authority.

It can take a country decades to recover from the economic impacts of hyperinflation, and if monetary policy is not corrected appropriately, it can easily reoccur.

Monetary Policy in Zimbabwe Between 1991 - 2008

The causes of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation crisis were several instances of policy mismanagement by Zimbabwe’s president Robert Mugabe and his government.

In the early 1990’s, the president instituted a series of economic reforms that proved disastrous. Poorly structured land reforms caused a sharp decline in food production, which raised food prices even as the banking sector collapsed due to economic sanctions imposed by the U.S., European Union, and the IMF. In 2000, the Zimbabwe government seized land from white farm owners and redistributed it to black farmers. However, many of the new owners lacked the experience and resources to maintain farm productivity. This led to a sharp decline in agricultural output.

The banking sector’s inability to mobilize funds for investments and loans was partly due to political looting by societal elites and government officials. Banks were also unwilling to loan money because of the increased risk due to political and monetary uncertainty. As a result, capital development and economic output sharply declined, and employment peaked at 80% during the inflation crisis.

In addition, the Zimbabwe government printed vast sums of new currency in order to finance military action in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as well as import enough food to reduce the risk of nationwide starvation. The gambit to ramp up food imports turned out to be another catalyst for hyperinflation as Zimbabwe found itself in greater debt—denominated in foreign currency. On top of this, no attempt was made by the Mugabe regime to curtail other forms of government spending.

The explosion in the volume of currency in circulation due to money printing caused a rapid increase in prices.

The severity of the hyperinflation in Zimbabwe was also due to institutional corruption and a lack of confidence in the government and currency. While printing currency to finance military efforts and food imports, the Zimbabwe government underreported its money printing activities by over 20 million dollars a month.

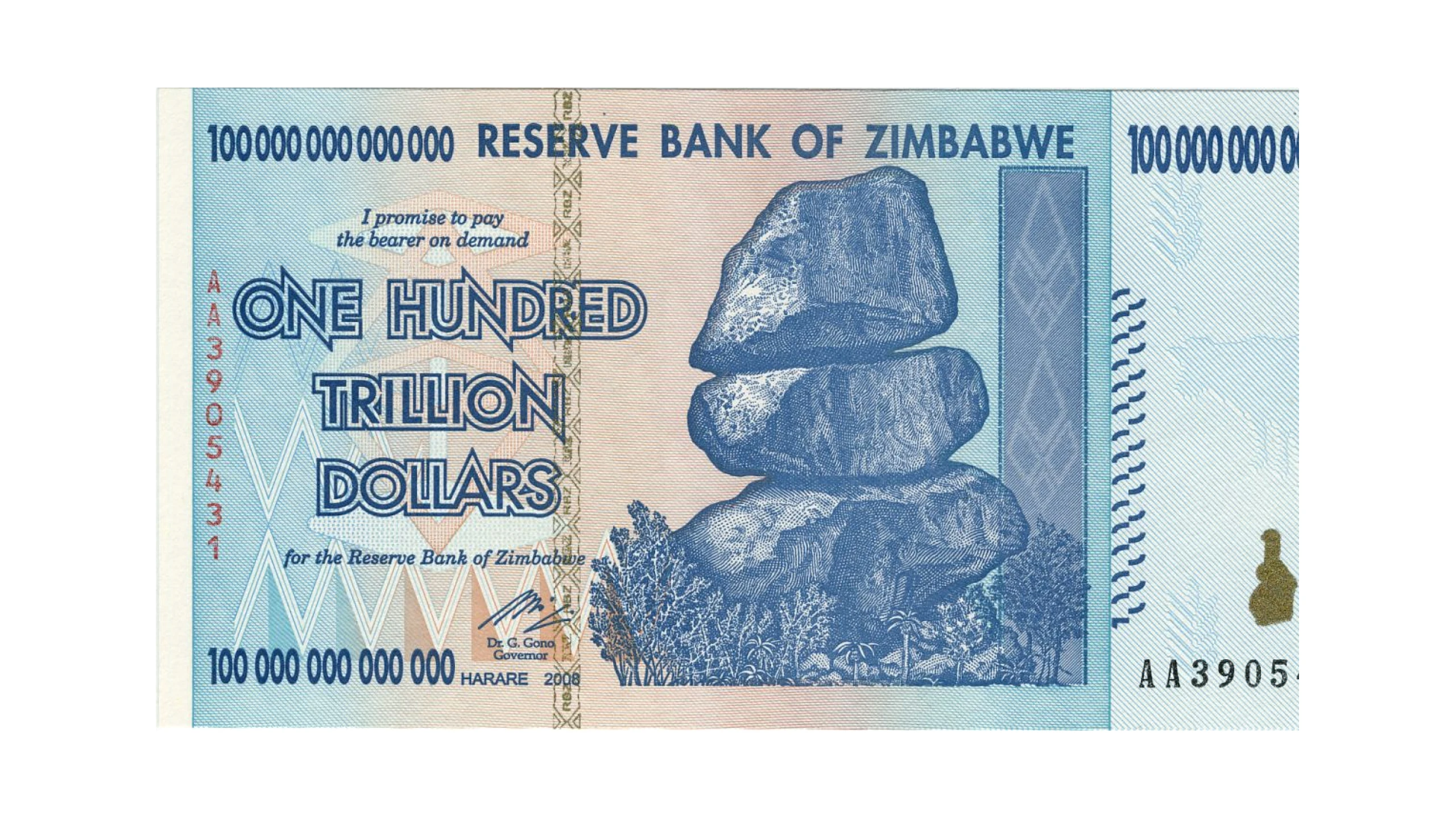

In an effort to correct the falling value of Zimbabwe’s currency, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe simply increased its money printing efforts, declared inflation illegal, redenominated its currency from Z$5, Z$10, and Z$20 bills into Z$100,000,000 and Z$200,000,000 bills, intentionally avoided updating its foreign exchange rates or inflation rates, and announced new currency regimes that did not address the underlying causes of inflation and further reduced citizens’ confidence in the stability of currency. The redenomination went so far that Z$100,000,000,000,000 (One Hundred Trillion) dollar notes were injected into circulation.

This made the Zimbabwean dollar virtually worthless, forcing people to barter goods or use foreign currencies for transactions. As a result, the black market for foreign currencies became a common method for obtaining basic goods and services at a relatively consistent value, despite the illegal use of foreign currency.

Economic Reform in Zimbabwe, 2008 - Present

As inflation hit all-time highs in late 2008, the Zimbabwean government began to institute several reforms. First, they adopted foreign currencies, including the U.S. Dollar and the Euro, as official currencies, which allowed them to stabilize prices, exchange rates, and rebuild confidence in the value of the currency.

Secondly, in 2009, the government stopped printing Zimbabwean dollars and allowed people to use the foreign currency of their choice, mostly U.S. dollars. This restored consumer confidence in currency values.

As a result, the inflation rate fell consistently for many years, hitting 4.3% in July 2018. Although the Zimbabwe Minister of Finance stated in 2015 that they would not attempt to reinstate a national currency, a new regime in 2019 announced a new Zimbabwe currency that has prompted a return of hyperinflation. This new currency was called the RTGS dollar (Real Time Gross Settlement). Indeed, the inflation rate was 417.25% inflation in October 2020.

What Is the ZiG (Zimbabwe Gold)?

The Zimbabwe Gold, also known as ZiG, is a new digital currency backed by Zimbabwe’s gold reserves. It has been the official currency of Zimbabwe since April 2024. While the ZiG is a digital currency, Zimbabwe also issues 22-carat gold coins that can be converted into cash, which serves as a physical counterpart to the digital currency. Therefore, the ZiG encompasses both a digital currency form and physical gold coins that can be converted into cash.

The idea is that the money supply will be limited to the amount of gold the country possesses, which would then theoretically prevent excessive inflation. This concept draws inspiration from the Gold Standard from the 20th century. However, maintaining a gold-backed currency also requires managing gold price fluctuations.

Skepticism about the ZiG remains due to the government’s history of underreporting money printing activities and misleading economic information. For the ZiG to succeed, the Zimbabwean government needs to regain the trust of its citizens, address past grievances, and demonstrate transparent and stable economic management.

Conclusion

After peaking at nearly 557% inflation in late 2020, the Zimbabwean dollar has returned to a more modest, double-digit yearly inflation rate. However, as recently as June 2023, annual inflation again climbed to triple digits and reached 172%. These figures are according to data from the IMF.

Time will tell how the nation will weather the seemingly endless storms of hyperinflation. But central bankers and central planners ought to heed history’s warnings: unrestrained money printing and irresponsible fiscal policy tend toward increased inflation. If left unchecked for long enough, the hyperinflationary spiral is nearly impossible to stop.

Key Takeaways

- Hyperinflation is defined as a monthly inflation rate greater than 50%.

- Zimbabwe experienced a decade-long period of hyperinflation due to poor monetary policy strategies.

- Hyperinflation increases the price level of goods, reduces incentives the save, and decreases confidence in government.